Craig Grossi is not sure what his life will be like without his dog, Fred, but he knows he can never stop talking about him.

“I owe that to everyone who has come to rely on Fred as a beacon of hope and possibility,” Grossi, 40, said from his Midcoast home near Damariscotta on Wednesday. “I’ll continue to speak at events and schools or wherever people want to hear a real-life story about a dog that taught a Marine to live again.”

Fred died of cancer at his and Grossi’s home on Nov. 22. He was 14. During his life, he survived war-torn Afghanistan then helped Grossi deal with post-traumatic stress disorder, a battlefield head injury and alcohol abuse. Grossi credits Fred with “saving” him by getting him to open up to others and ask for help.

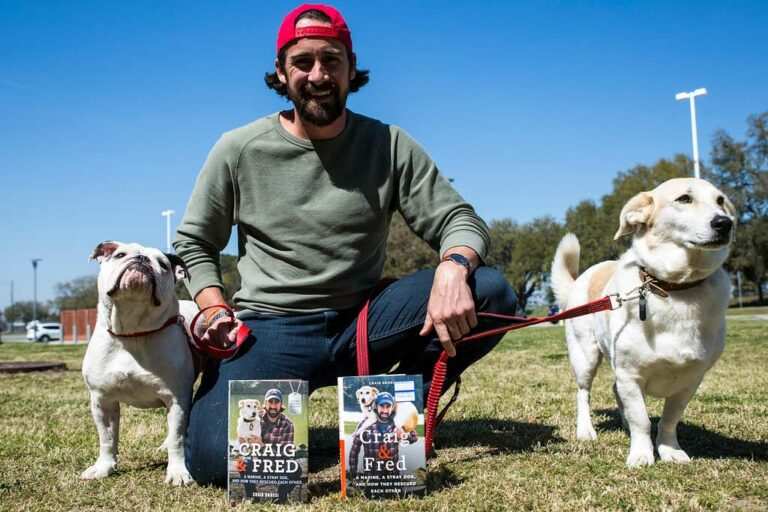

Fred also was the subject of two books by Grossi, “Craig & Fred,” published in 2017, and “Second Chances” in 2021. The books got national attention and made the pair in-demand speakers at schools, libraries, prisons and many other places. Fred became a social media star, with 94,000 followers on his Instagram account, fredtheafghan.

Since Fred’s death, Grossi has been heartened by the outpouring of support and sympathy from people all over the country, on Instagram and Facebook, who wrote about how Fred had inspired or helped them in some way.

“You made the world a brighter place with the thousands of paw prints you left on so many of our hearts,” one commenter wrote on the Fred The Afghan Facebook page. “In this sometimes dark world, you were a shining star for those of us who were able to read about your amazing journey. Thanks to the incredible human that saved you.”

Grossi was planning to write a third book tentatively titled “Expedition Fred,” about a trip they took to Alaska in September and October. That third book will now be more about Fred’s life, with the Alaska trip a part of it, and probably will have a different title.

Grossi said he likely will plan some sort of event in Fred’s memory in the spring. Not only did thousands of people know Fred from social media posts, but many also got to meet him in person, since he and Grossi were constantly being invited to speak all over the country.

“He was such a lovely creature, watching the kids with him was always so beautiful,” said Jacqui Davison, a farmer from Hillsboro, Wisconsin, who organized a townwide reading of “Craig & Fred” and then invited the pair to speak at a local school. “The kids thought Craig was cool, but Fred was like a movie star. He’d find a kid to sit next to and that kid would be floating on air the rest of the day.”

While Grossi knows now that Fred’s story can inspire and help people, he didn’t want to tell it, at first.

Grossi stumbled upon Fred in an Afghanistan combat zone in 2010, just after Grossi and his fellow Marines had held off a much larger Taliban force for a week. Grossi sensed something special in the dog, a “stubborn positivity” in the face of constant gunfire and bloodshed.

While other wild dogs in the area snarled and growled at the soldiers, Fred wagged his tail and accepted treats of beef jerky and happily approached the Marines. When another soldier took a bullet to the helmet, sustaining a traumatic brain injury, Fred came to his bedside every hour or so for a snuggle.

When it was time to leave Afghanistan, Grossi couldn’t bear to leave Fred, so he smuggled him aboard a military flight and took him in. He moved to Washington, D.C., where he’s from originally, and worked for the federal Defense Intelligence Agency.

Grossi struggled with the transition and spent too much time in bars. He didn’t talk to anyone about what he was going through or seek help. But he’d take Fred to dog parks where other dog owners would always ask about the perky, friendly dog. His looks are unique — a face sort of like a Lab, short legs like a Corgi — so they’d always ask: “What breed is he?”

Grossi did not want to relive his experiences in Afghanistan, where he saw friends die. So he’d make up a breed, like “Pocket Wolf,” to avoid telling Fred’s real story and relive the trauma of combat. (Grossi had Fred’s DNA tested years later and found out he’s a West Asian Village Dog.)

People continued to ask about Fred. One day at the dog park, Grossi finally decided to talk about how Fred came into his life and what he had meant.

“Something in me just said, ‘Tell the story.’ So I told the story, and people I met encouraged me to tell it to others,” said Grossi. “We’d be at the park, Fred chasing squirrels, and people would be waiting for me to tell Fred’s story. The more I told it, the more connected I felt, the more confident I began to feel. “

It was while telling the story of Fred at a dinner in Boston that he met his wife, Nora Parkington.

One of the many places where Fred and Grossi shared their story over the years was at the Maine State Prison in Warren, where they made regular visits with inmates, including veterans, who trained service dogs. Grossi also led a writing group at the prison, with Fred by his side. Both inmates and guards were inspired by their story, said Randall Liberty, commissioner of the Maine Department of Corrections, who helped arrange Grossi and Fred’s prison visits.

“I think the powerful relationship between Fred and Craig and their backstory — Craig saving Fred and then Fred saving Craig — is something that speaks to a lot of people,” said Liberty. “It shows how people can heal together by talking about the past.”

___

(c) 2023 the Portland Press Herald

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

0 comments :

Post a Comment