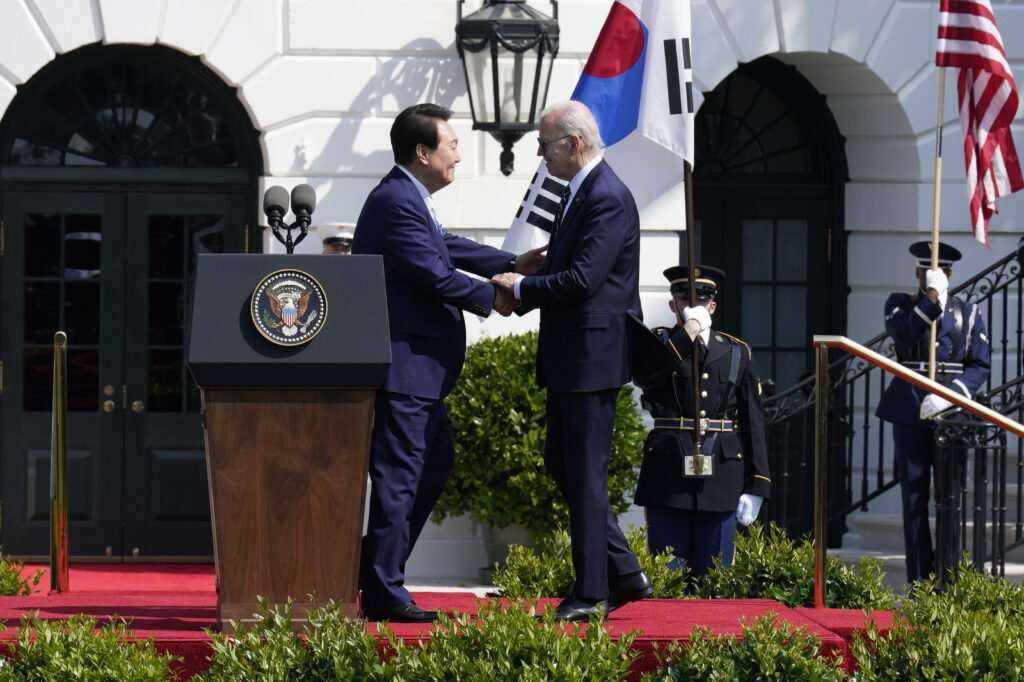

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol has received the red-carpet treatment this week as Washington and Seoul mark the 70th anniversary of their alliance. Yoon‘s weeklong itinerary features a high-profile summit with President Joe Biden, a glittering state banquet — an honor reserved only for the United States’ closest allies — and a joint address to Congress.

But beneath the pomp and ceremony, thorny issues are at stake. South Korean companies are worried about how Biden’s efforts to promote American manufacturing and limit the growth of China’s high-tech sector might affect them. And earlier this year, a leak of classified Pentagon documents revealed details of U.S. espionage against South Korea, embarrassing both countries and causing political headaches for Yoon.

Both countries are also hoping to counter North Korea’s aggressive missile testing. The two leaders on Wednesday will unveil a new agreement to bolster extended deterrence, the idea that the U.S. will defend its allies with its full military capabilities — including nuclear ones — in response to mounting threats from North Korea, according to senior administration officials. The “Washington Declaration” will give South Korea more insight and input into U.S. military planning in exchange for Seoul’s commitment to not develop its own nuclear weapons, according to officials.

The U.S. will also send a ballistic missile submarine on visits to South Korea for the first time since the 1980s as a visible demonstration of U.S. military might, officials said. The two leaders are expected to roll out a suite of other initiatives on cybersecurity, economic investments and other areas of cooperation to further solidify the alliance in the face of North Korea’s record number of nuclear missile tests this year.

Yoon’s visit is a “springboard for connecting Korea to this broader web of alliance relationships in the region, whether we’re talking about security cooperation, economic security issues … and interacting with other stakeholders in the region, including Southeast Asian countries and Pacific Islands,” said Nicholas Szechenyi, deputy director for Asia at Washington-based think tank the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Yoon, a conservative politician who came to office last year, has made fortifying military and diplomatic ties with the U.S. a centerpiece of his foreign policy. He resumed joint military exercises with the United States, coordinated with the U.S. to decrease reliance on China for global supply chains and, more critically, thawed relations with Japan despite a bitter historical dispute over Korean forced labor during Tokyo’s colonial rule — a decision that prompted domestic backlash.

Biden, too, has tried to shore up U.S. influence in the Indo-Pacific region as Washington has intensified its economic confrontation with China. Biden will host Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. at the White House next week, and is set to travel to Japan for the Group of Seven summit in Hiroshima on May 19-21.

Although North Korea is a priority for the alliance, it’s a perennial issue that both countries are aligned on, according to Victor Cha, Korea Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“The text of it is obviously to deal with North Korea, but the subtext is China,” Cha said.

Biden has tried to quiet South Korean companies’ concerns about their ineligibility for subsidies under his Inflation Reduction Act, which provides tax credits for electric vehicles that are assembled in North America or include key components that are sourced domestically. South Korean companies do not currently qualify. Before Yoon arrived at the White House, General Motors and South Korea’s Hyundai announced billions in new investment to produce electric vehicle battery cells in the U.S. with South Korean battery makers.

But Biden will have to resolve frictions over the $50 billion CHIPS and Science Act. The law gives federal funds to semiconductor manufacturers that agree to limit advanced chip production in China over the next 10 years. U.S. export controls on computer chip equipment designed to choke China’s access to the advanced technology have also rankled Seoul. Japan and the Netherlands have imposed similar restrictions.

South Korean companies Samsung and SK Hynix received a one-year exemption from the export ban, but both countries will have to negotiate a solution when it expires in October.

“South Korea is very much reliant on its semiconductor industry as part of its broader economic strength and that industry is heavily invested in China,” said Frank Aum, an expert on Northeastern Asia at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Yoon is under pressure to return from his visit to the White House with further assurance of Washington’s dedication to trade arrangements and defense against the nuclear-armed Pyongyang as he looks to smooth over relations in the wake of the leak of classified documents.

The leaked intelligence showed top South Korean officials were concerned that ammunition South Korea sold to the U.S. would wind up in Ukraine, violating the country’s policy of not supplying lethal aid to countries in conflict. The revelation prompted criticism back home but White House officials have brushed off any tensions caused by the breach.

Scott Snyder, senior fellow for Korea studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, said today’s relationship with Seoul has to be “an alliance powered by chips, batteries and clean technology” but that there are “drag” issues that complicate ties, including the South Korean public’s reluctance to get involved in Ukraine and recently leaked U.S. Pentagon documents.

“And so it’s a little bit ironic, because I think that the alliance is probably at its highest point that it’s been, maybe in the (70-year) history of the alliance in terms of intensity and depth of coordination and … breadth of scope,” Snyder said. “And yet, at the same time, there are these underlying issues of trust that are there that could trip things up and might have a negative impact on President Yoon’s public approval.”

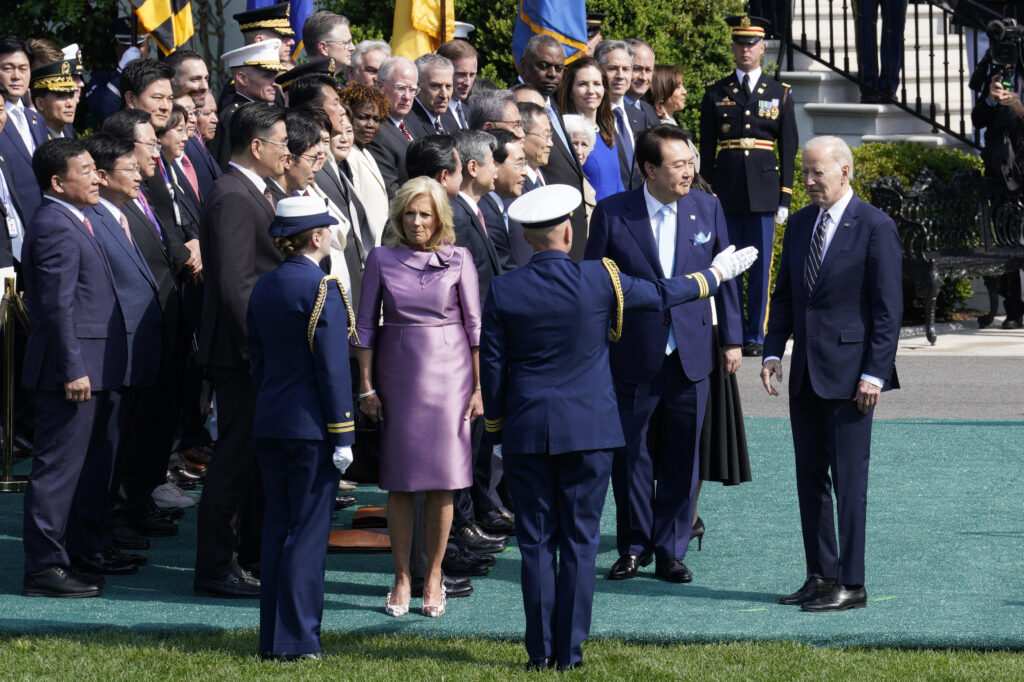

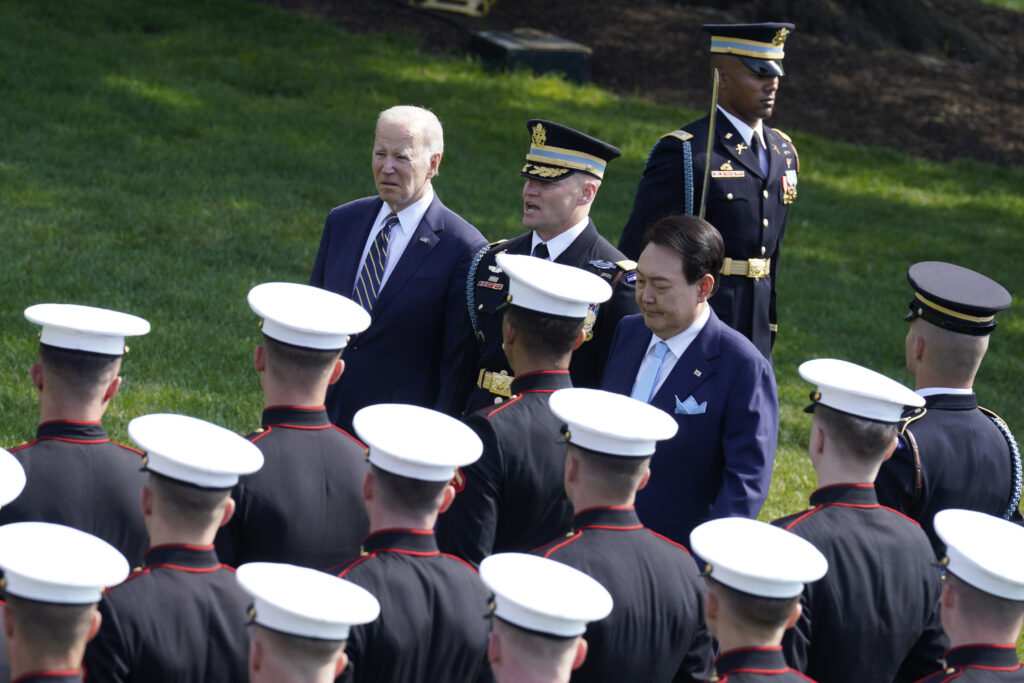

Yoon opened the six-day visit on Tuesday by touring a NASA facility with Vice President Kamala Harris and later laying a wreath at the Korean War Memorial with his wife, Kim Keon Hee, and Biden and first lady Jill Biden.

He also met with Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarando, who announced the streaming giant would invest $2.5 billion in Korean entertainment over the next four years. Yoon is expected to meet with other studio executives from Disney, Sony Pictures and others at the Motion Picture Assn. headquarters in Washington on Thursday.

“It’s a new frontier for the alliance beyond the sort of traditional security and free trade components of the relationship,” Cha said.

___

© 2023 Los Angeles Times

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

0 comments :

Post a Comment