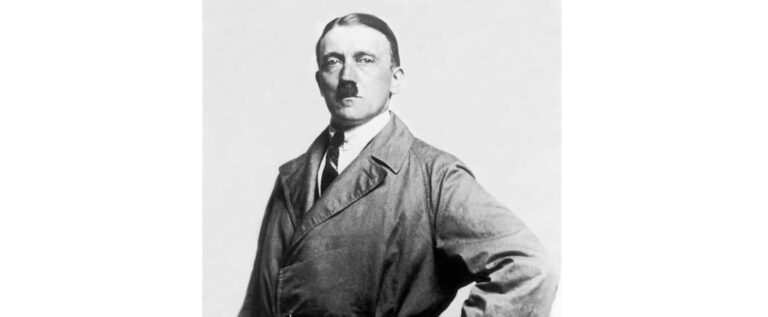

Eighty years ago this month, some of the darkest hours of the Holocaust emerged as, on the day before Hitler’s birthday, German troops invaded the Warsaw ghetto in Poland and cruelly massacred and deported thousands of Jewish residents.

As that atrocity took place, 13-year-old Wilhelm “Willi” Langbein was on the verge of being torn from the loving arms of his family in Witten, Germany, and shipped south to the Swiss border. He was to reside “for his safety” with a German family in Konstanz but, in reality, underwent military indoctrination.

He had no knowledge of the persecution of the Jews, other than he suddenly had been forbidden from visiting his Jewish friend in his hometown. He had inquired about why Jewish residents were wearing yellow stars on their sleeves, but his questions were brushed aside.

The Nazis had created two organizations for young boys: the Deutsches Jungvolk, for boys between ages of 10 and 13, and the Hitlerjungend (Hitler Youth), for ages 14 to 18.

Parents were required to relinquish their young boys to these “vacation” groups when the call came. It reportedly was to protect them from Allied bombs, but the more sinister truth was soon evident after Willi arrived at his new home and began being indoctrinated into the service of the Hitler regime.

Willi was 14 when he was sent into battle in mid-1945. He was told to sacrifice himself for der Führer and his country, says Heidi Langbein-Allen, Willi’s daughter, who lives in Escondido. “They were taking these children and turning them into cannon fodder.”

Her late father, who miraculously survived the war despite being wounded and captured by the Allies, was one of the myriad victims of World War II and Hitler’s insatiable aggression.

“When he returned from war and discovered what really had happened, he felt horrified, violated and extremely angry. He got very depressed. He began dedicating his life to do his part to ensure that what had happened would not happen again,” says his daughter. She felt compelled to learn more about her father’s story before he passed away five years ago in his native Germany.

Like many soldiers who carry a heavy burden of guilt, he didn’t share his war experiences with his family, Langbein-Allen notes. She pressed him to tell his story.

When he was in his 70s, he became worried by a re-emergence of nationalism and extremism in Eastern Europe and Middle Eastern countries and decided to break his silence.

He recorded 16 tapes. They were in German, and his daughter planned to translate them to share with family members … but life intervened.

“Nine years passed, and it was 2016. My father was not in good health and was in a residential facility,” she says. Events were continuing to polarize the world, and she felt a sense of urgency to translate the tapes while her father was still alive.

She mentioned her project to a friend at Solar Turbines, where she works as a trade compliance manager. “That’s a book, and you need to share it,” her colleague advised.

She searched for firsthand accounts of World War II from former Hitler Youth members but found little. It was almost taboo to talk of the German experience because of the overwhelming catastrophe Germany had orchestrated, she explained.

“History is a kaleidoscope of facets. You have to have all the pieces for a full understanding of all sides of the story — especially if you want to keep it from happening again.”

She enrolled in a writing course through San Diego Writers, Ink and began a six-year project of ghostwriting and publishing her father’s story. She used his recollections and words, adding explanatory notes with historical perspective as needed.

When Willi was only 8, he got the first inkling that something was wrong when the synagogue next to his school was burned. He heard his parents speak in worried, hushed tones but they evaded his questions. Something momentous had happened, but he didn’t know what.

It was Nov. 9 and 10, 1938, which would go down in history as Krystallnacht, (night of broken glass), a Nazi-coordinated wave of antisemitic violence.

Langbein-Allen titled her dad’s memoir, “Save the Last Bullet,” because German commanders had instructed their young recruits that, if captured, they were to shoot themselves rather than be taken prisoner.

Willi spent a year with the Vollmar family in Konstanz, a civilian family ordered, along with other families, to take in the boys. When he turned 14, military training began in earnest and soon SS recruiters relocated some of the boys to the eastern battle front where the German army was trying to repel the advancing Russians.

“Boys, a great privilege is being bestowed on you today by the Führer,” three Waffen-SS Panzer troop commanders told the schoolboys. “‘Today, we are going to select a few of you to receive valuable military training so that you can defend our Fatherland against the Bolshevik threat, the enemies of the Reich who want to destroy us.”

Willi recalled: “We listened in awe. It was a great honor to be chosen to defend our country, and it made us proud. My mind replayed the newsreels that reported on the evil Allied forces that wanted to finish us, first by bombing all our cities to kill all civilians, then by torturing and starving the survivors, and the heroic efforts our soldiers were making to protect our mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters … Our teachers and our schoolbooks told us that we were Germany’s hope and its future.”

Willi was relocated to Schleching near the border with Austria and Hungary. It was March 1945 and the Germans were fast losing ground, but the fresh-faced recruits had no inkling of this.

Willi’s assignment was to use a Panzerfäuste anti-tank rocket launcher to take out as many tanks as he could while hiding in a foxhole directly in the path of the deadly machines.

A tank had to be hit with the launcher’s single round at precisely 20 meters — if it was farther away, the explosive wouldn’t be effective, and if it was closer, the shooter was likely to perish in the explosion.

Willi survived, only to face the threat of death at the hands of the SS as a suspected deserter during the beaten soldiers’ retreat. He was taken prisoner by American troops and sentenced to a year of farm labor.

It was only during internment that he learned the truth about the war and the atrocities committed by Hitler’s troops.

“He was profoundly shocked and in denial,” says his daughter. “At first they believed it was American propaganda. It was so awful, it couldn’t possibly be true.”

At 15, he returned to Witten, where his home had been destroyed and most of the city flattened by bombs. He re-enrolled in school after a two-year gap in his education.

He went on to law school, entered the German foreign service and spent the rest of his life trying to make amends. Willi married a woman from Spain who had been his Spanish-language pen pal and they had two children.

In 1979, he earned the European Union’s medal of European Merit for his work to advance democracy and unify Europe and spent the final years of his career as the head of a German legal contracts division within NATO.

“He determined he was going to make a difference,” says Langheim-Allen, impressed that he had the fortitude to turn all that darkness into light. As fate had it, she married a member of the U.S. Navy (now retired) who she met while vacationing in Italy. They moved to San Diego in 1985 and spent 25 years in Poway before relocating to Escondido two years ago.

At the end of 2020, the first-time author submitted her manuscript to 12 independent publishers. She received responses from six and publishing offers from four. She selected British publisher, Pen and Sword Books, which specializes in military history.

Sadly, her dad died in 2018 and never read his completed memoir.

What’s next in Langbein-Allen’s literary career? She now is writing a fictional history of her mother, who grew up under the Spanish regime of dictator Francisco Franco and has her own story to tell.

___

© 2023 The San Diego Union-Tribune

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

0 comments :

Post a Comment