This article was originally published by Radio Free Asia and is reprinted with permission.

Feeling disheartened about the future, Chinese graduate student Qi Cui took an online quiz a few years ago that suggested she was depressed. She thought she would feel better once she started her new job and the COVID pandemic eased.

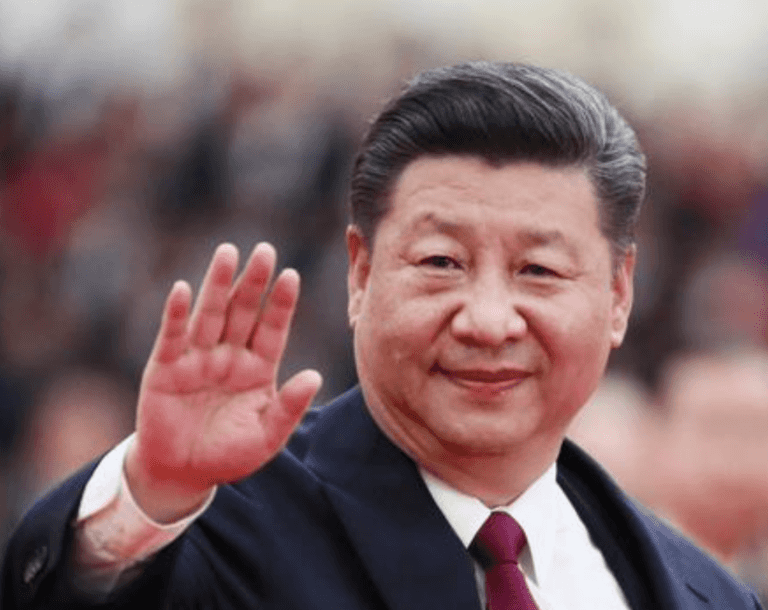

But the sense of despair has persisted, and even worsened. Now, as she reads the news about Xi Jinping’s tightening grip on power and China’s intensifying clampdown on dissent, she realizes something more is going on.

Qi, who is in her early 30s, has concluded that she is experiencing something many on Chinese social media are calling “political depression” – a deep sense of hopelessness that they can change or influence the government, and that attempts to speak out are pointless.

“Political depression eventually winds up with just feeling numb,” she said. “I have gone from being shocked and angry and feeling that I have to say or do something, to the realization that I may not be able to change anything.”

“When you’re Chinese growing up in mainland China, you’d have to be wicked or ill-informed not to suffer from at least a bit of political depression,” said Qi, who opted to use a pseudonym for fear of reprisals arising from giving interviews to overseas media.

“Everything has been ruined by the outrageous behavior of the government,” she said.

Crushed hopes

The term emerged in Chinese discourse during the lockdowns, mass quarantines and compulsory daily testing under the zero-COVID policy.

Chinese state media even published some articles during that time advising people how to manage political depression, but focused only on the pandemic measures, not on anything political or deeper.

Today, the phrase is widely found on Weibo, a Chinese microblogging site, and surfaces regularly in private conversations between people, sources inside the county tell Radio Free Asia.

The Chinese website Huxiu listed “political depression” as one of last year’s key psychological phrases.

Signs of hope and change flickered briefly in late November, during the protests across more than a dozen cities in solidarity with the Uyghur victims of a fatal lockdown apartment blaze, and more widely against the lack of freedom of expression in the country.

But within days the protests faded, and since then dozens of young Chinese – many of them women – have been detained for taking part in the “white paper” protests, in which people held up white sheets of paper to reflect their voicelessness.

Feeling suffocated

A college student in China who gave only the surname Zhang for fear of reprisals said he feels as if he’s being suffocated, unable to cry for help or make any sound at all.

“It feels bad, but there’s also a feeling of helplessness,” Zhang said. “I often vent outside the Great Firewall and also to my friends circle [on WeChat], and with a sarcastic or negative attitude.”

The Great Firewall uses a combination of blocks, filters and human censorship to limit what Chinese users can see or do online, and Chinese nationals are under huge political pressure not to complain about China overseas, lest they give ammunition to “hostile foreign forces” that are allegedly trying to bring down the Chinese Communist Party.

Zhang’s personal experience of “political depression” stems from an experience in high school, where he complained about the violation of students’ human rights, leading to retaliation from the authorities.

Since then, he has turned his attention to researching other attempts to stand up for human rights in China.

“I read all of the reports from The People’s Daily dating from April 15 to June 4, 1989,” Zhang said, referring to the time period of the Tiananmen Square massacre, which the government has tried to cover up. “I was so sad and felt so helpless; I wanted to cry.”

He said he had once believed that economic openness would naturally bring about political reform and progress towards democracy.

Now he feels that he might have been better off not knowing how much better things could be.

‘This is just a fantasy’

A Chinese woman currently studying in Boston, who gave only the nickname Kayla, said she had grown up in a household where political indifference was the norm.

Talking to her parents about politics was like throwing rocks into deep water. “There was no response,” she said.

“When I was younger, I thought that I could bring about change,” she said. “After all, I would grow up, start work, and take part in various forms of activism.”

“Then I found out that I didn’t have the right to do that,” she said. “Most people in junior high school were fully intending to come back to China, to help build the country’s future.”

“Then you figure out that this is just a fantasy, and will never come true.”

For Kayla, the low point came when China’s rubber-stamp parliament, the National People’s Congress, nodded through changes to the country’s constitution abolishing presidential term limits, paving the way for indefinite rule by Communist Party leader Xi Jinping.

By the time that lone protester Peng Lifa hung banners calling for Xi’s resignation and democratic elections from a Beijing’s flyover ahead of the 20th party congress on Oct. 13, Kayla couldn’t hold in her tears.

“I remember that I was eating at the time, and the tears were just rolling down my face, and I couldn’t eat another thing,” she said.

“I was just chatting, and then suddenly I lost control of my own mind .. I felt awful, so guilty and so depressed,” Kayla said. “I also had excessive anxiety, worrying about how things would turn out.”

‘A ceiling on one’s possibilities’

Shayna Mell, a licensed psychological counselor in the United States, said political depression seems to include feelings of hopelessness, helplessness and powerlessness, as well as symptoms similar to sadness.

The experience leaves many feeling frustrated and exhausted, as if they have a bleak future ahead of them.

She said authoritarian governments can exacerbate depression with strict censorship, controls on content and official propaganda.

People who are prone to political depression will look on in horror, deprived of any agency, amid growing uncertainty and despair, Mell said.

Psychologist Robert Lusson wrote a HuffPost article in 2017 that described political depression as including “the perception that work, education, imagination and perseverance do not matter, and that there is a ceiling on one’s possibilities.”

He said it may be a type of depression that meets the requirements of the American Psychological Association for depressive disorders.

‘Huge debt’

Kayla is now in therapy, where she talks about her country’s political life as much as about her personal life.

“But when you are depressed, you want to watch and read more [of the news], and want to know more about what’s happening and what other people think. It’s like an obsessive behavior,” she said, adding that this is also a way to feel that she is somehow in control.

Qi Cui and Kayla both reported feelings of survivors’ guilt on reading reports of those who have been detained for speaking out.

“Chinese people overseas owe a huge debt to the young people inside the Great Firewall who took part in the white paper movement,” Qi said. “But now there is more political depression among young people in China as a result, and they will pay a higher price for it.”

Despite all of that, Kayla still takes part in protests relating to China from overseas, while Zhang is convinced that regime change is only a matter of time.

“All of us here are determined to protect ourselves, to protect our health, so that we live to see that day come, and to set off firecrackers,” he said.

0 comments :

Post a Comment